尾声

令人难以置信的是,统治中国边疆地区的蒙古可汗之令,竟能压低英国市场的鲱鱼价格。

——爱德华·吉本

《罗马帝国衰亡史》,1776—1788年

10世纪的董保德并不是丝绸之路的终点。事实上,有些人辩称直到今天丝路仍存在。 [1] 因此,本书的尾声不过是想要告诉大家,在这些传奇故事发生之后,1000—1400年间书里讨论的某些主题大概经历了什么变化,同时为那些想要进一步了解的读者提供一些阅读线索,而下文提及的事例就大多发生在13世纪。在这几个世纪中,许多新势力崛起又覆灭,有些几乎淹没在历史长河里,如传奇故事里提到的于阗及其他塔里木王国。虽然史料中仍出现它们的名字,但考古遗存所见证的历史要比这多得多,遗存中常见的写本就是用当地失传已久的语言写成的。例如,在1227年成吉思汗(同年去世)灭西夏以前,西夏王国的范围从敦煌一直延伸到蒙古草原的边界,这片广大的地域曾在党项族的统治下长达两个世纪。 [2] 从西夏边城哈拉浩特(译注:即黑水城 )的一座佛塔中发现了一万余卷写本及早期刊本,这批文献目前尚未被完全编目,也还没得到充分的研究。近年来,考古人员对银川附近的西夏都城与皇陵开展调查,为我们提供了丰富的新材料。 [3]

其他文明对中亚的影响则更为显著也更持久,特别是突厥与蒙古汗国,其统治范围从中国边境、塔里木盆地一路延伸至印度,并横跨欧亚大陆。 [4] 喀喇汗王朝皈依伊斯兰教后不久,于1006年拿下于阗。 [5] 库曼—钦察联盟和塞尔柱突厥扩张至位于欧洲边缘的西亚,前者在草原一带称霸,后者则深入伊朗和安纳托利亚地区。 [6] 突厥人还在北印度的德里建立苏丹国, [7] 蒙古人也从大草原一带向西扩张,建立起一个无可匹敌的欧亚王朝。 [8] 随着13世纪蒙古的崛起,横跨欧亚的贸易与旅行开始繁荣起来,通过陆路、海路继续与北非和东非保持联系,与欧洲的来往则靠河道、海路和陆路来维持。 [9]

丝绸仍然价格不菲,生丝与丝绸在欧亚大陆已有多个生产中心,而且产量不断增加。中国虽然仍在出口生丝与丝绸,但早已失去了垄断地位。蒙古人对丝绸的需求量十分惊人,他们在塔里木盆地建立了新的生产中心。 [10] 意大利日益控制了销往欧洲的丝绸贸易,这些丝绸从草原陆路或从海路运来,很多都是通过黑海和枢纽地克里米亚到达欧洲的。 [11] 旅人可以方便地跨过整个蒙古帝国,这也为肆虐欧亚大陆的瘟疫传播提供了契机,造成数百万人死亡。 [12]

蒙古人有着自己的传统信仰,但如果别的宗教能适应其统治的话,他们也表现出一定的宽容。 [13] 伊斯兰教的进一步扩张,成了这时期的一个显著现象。伊斯兰教的传播靠的不是阿拉伯人的征战,而是突厥人的皈依与征服。科技、经济、艺术和文化也因此继续传播与发展。 [14] 尽管到了14世纪,塔里木盆地大部分地区都已经伊斯兰化,但仍保持宗教的多样性,例如马可·波罗曾记载今喀什和莎车一带的景教社群, [15] 佛教也还在青藏高原盛行。13世纪蒙古的伊利汗国曾短暂信奉佛教,但后来皈依了伊斯兰教。 [16] 佛教主要流行在丝路的东端,即东南亚、中国、日本和韩国,而在其起源地印度次大陆,佛教却在不断衰落。 [17] 不过,因宗教迫害而从波斯逃亡出来的祆教社群,即帕尔西人,却在此找到了新的家园。 [18] 他们融入当地的印度教、耆那教及伊斯兰教社群。8世纪,船长传奇开始时,阿拉伯商人便将伊斯兰教带到印度的沿海城市;到10世纪,画师传奇结束时,突厥人则把伊斯兰教传到了北方。 [19] 在被奥斯曼帝国攻陷以前,基督教以君士坦丁堡为据点,主宰着世界另一边的欧洲。阿克苏姆至今还保持着基督教信仰,但在非洲东岸进行贸易的斯瓦希里人中,伊斯兰信仰是主流。 [20]

如书中传奇故事的旅行者一样,在外交、贸易、信仰的推动下,人们往来于蒙古帝国的宫廷,其中有好几个留下了相关记录,包括圣方济各传教士若望·柏郎嘉宾(Franciscans John of Plano Carpini,1182—1252)和威廉·鲁布鲁克(William of Rubruck,约1220—约1293)、商人马可·波罗(1254—1324)、朝圣者伊本·拔图塔(Ibn Battuta,1304—1368/1369)。 [21] 蒙古宫廷的景教僧人拉班·扫马(Rabban Sauma,约1220—1294)还前往欧洲游历。 [22] 当时最详细的一部编年史是由波斯史学家拉施都丁(Rashīd al-Dīn,1247—1318)撰写的。 [23] 当然,在丝路沿线居住或旅行的人更是不计其数,如士兵、商人、僧尼、公主等等,但他们留下的生活痕迹最多只是蛛丝马迹。

这一时期的陆上交通模式并没有发生巨变。最快的交通方式仍然是骑马,早在千年以前草原骑兵便证明了这一点。此外,根据不同的地形与财富水平,人们还可以选择骆驼、牦牛、牛车、驴子和步行等方式。现代海洋考古的新进展,以及最近的大发现,证实了印度洋的海上贸易一直持续到公元第二个千年。同样不变的还有海上贸易的风险,货船连同其满载的各式货物随时可能沉入海底。公元第一个千年的最后两百五十年,中国发明了瓷器。欧亚大陆对瓷器的需求并不亚于丝绸,但与丝绸相似,几个世纪后瓷器的生产技术才传播开来。 [24] 阿拉伯、中国和东南亚的商船运载大量陶器(珍贵的瓷器很少见)销往外地,其市场可远达非洲沿岸。 [25]

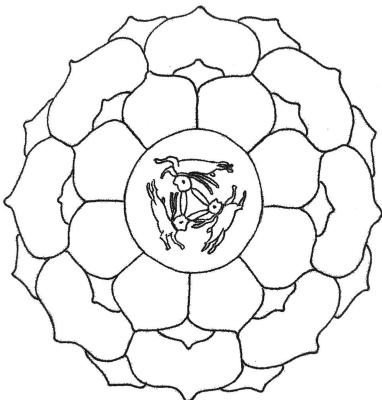

图37 敦煌莫高窟第407窟顶莲心的三兔图案,6世纪晚期。(作者绘)

跟从前一样,还有大量的别的货物在贸易之列:截至13世纪,地中海地区有专门买卖中亚奴隶的市场 [26] ,伊朗则有市场销售中国出产的大黄和茶叶 [27] ;而在中国的一些市场,人们能买到非洲和印度的象牙。在蒙古人的统治下,汉人可以享用伊朗的雪酪和穆斯林的饺子汤。饺子汤的材料就有羊肉汤、蒙古的奶酪和西亚的豌豆。 [28] 从德里到伦敦,贵族都穿上金线刺绣的蒙古式衣衫; [29] 伊朗的伊利汗国模仿中国的做法,开始使用雕版印制的纸币。 [30]

丝路东部沿线的一些石窟里,本生故事(佛祖的前世故事)成了装饰洞窟的壁画题材。这些故事还通过某种渠道,出现在新版的《伊索寓言》里。 [31] 同时,6至7世纪敦煌石窟顶部的三兔共耳图,竟出现在12世纪的伊朗金属器上,乃至1281或1282年伊儿汗国的铸币上。 [32] 到13世纪,三兔共耳图传到了基督教盛行的欧洲,频频在教堂中亮相,其后这个图案还被用来装饰犹太教堂。正如现代一位学者所说的:“蒙古帝国在一个多世纪里,一直是旧大陆最重要的文化交换中心。” [33]

在这个互相联结的世界里,连那些生活在社会边缘的群体也将自己视为其中一分子。根据13世纪英国编年史家马太·巴黎(Matthew Paris)的记载,腓特烈二世(Emperor Frederick II,1194—1250)时期的商人曾航海至印度。他还认为,1238年蒙古对俄国的入侵,影响了英国的鲱鱼市场。这次侵略威胁到了诺夫哥罗德在波罗的海及北海一带的商贸活动,使得其商人不敢前往英格兰购买鱼货,造成英国市场供过于求,卖家不得不调低价格。 [34] 几个世纪后,这一事件令18世纪英国史学家爱德华·吉本感到困惑,但这并非是唯一的事例。亚非欧大陆仍紧密联系在一起,普通人在生活中——哪怕是一些微小的层面——仍可接触到来自远方的文化、技术与商品。

[1] 在本章的阅读方面,丹尼尔·沃(Daniel Waugh)给了非常有用的评价和建议,在此表示感谢。关于丝路的延续,见James A. Millward, Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang , p. 110。关于这时期欧亚大陆的联系,进一步的讨论参见Philip Curtin, Cross-cultural Trade in World History, Cambridge, Engl.:Cambridge University Press, 1984;Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System, AD 1250–1350 , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989;Jerry H. Bentley, Hemispheric Integration, 500–1500 C.E., Journal of World History 9, no. 2 (1998), pp. 237–54。

[2] 关于西夏的历史,见Ruth W. Dunnell, The Great State of White and High: Buddhism and State Formation in Eleventh-Century Xia , Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996;Y. I. Kychanov, “The Tangut Hsi Hsia Kingdom(982–1227),” in History of Civilizations of Central Asia , vol. 4, edited by M. S.Asimov and C.E. Bosworth, Paris: UNESCO, 1998, pp. 206-14。关于蒙古的征服之旅,见Ruth W. Dunnell, “Xi Xia: The First Mongol Conquest,” in Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire , edited by William W. Fitzhugh, Morris Rossabi,and William Hon-eychurch, Media, Pa.: Dino Don, 2009, pp. 153-62;Kepping,Ksenia, The Guanyin Icon: Chingghis Khan’s Last Campaign, paper given at the Circle of Inner Asian Art, SOAS, London, May 16, 2001,修订版见 http://kepping.net/raboty-15.htm。关于西夏的艺术,见Mikhail Piotrovsky ed., Lost Empire of the Silk Road: Buddhist Art from Khara Khoto (X–XIIIth Century), Milan: Electa and Thyssen-Bornemisza Foundation, 1993。

[3] 很多西夏的写本和印版都已经数字化,可在http://idp.bl.uk和http://eap.bl.uk浏览。关于早年发现的写本,见T. I. Yusupova, “P. K. Kozlov’s Mongolian and Sichuan Expedition (1907–1909): The Discovery of Khara-Khoto,” in Russian Expeditions of Central Asia at the Turn of the 20th Century , edited by I.F.Popova, Saint Petersburg: Russian Academy of Sciences, 2008, pp. 112-29;Y.I. Kychanov, “The Tangut Hsi Hsia Kingdom (982–1227)”。诸如墓葬这类的发现,见Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt, “The Tangut Royal Tombs Near Yinchuan,”Muquarnas 10 (1993), pp. 369–81。

[4] 到蒙古时期为止与中国接壤的政权,参见Herbert Franke and Denis Twitchett eds., The Cambridge History of China , Vol. 4: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368 , Cambridge, Engl.: Cambridge University Press, 1994。关于辽国,见Denis Twitchett and Klaus-Peter Tretze, “The Liao,” in The Cambridge History of China , edited by Herbert Franke and Denis Twitchett, 4, Cambridge, Engl.:Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 43-153;Shen Hsueh-man, Gilded Splendor: Treasures of China ’s Liao Empire (907–1125) , New York: Harry N.Abrams, 2006;Naomi Standen, Unbounded Loyalty: Frontier Crossing in Liao China , Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007。关于突厥人和蒙古人的论文,见Reuven Amitai and Michael Biran eds., Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World , Leiden: Brill, 2005。关于中亚诸国,见Denis Sinor, The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia , Cambridge, Engl.:Cambridge University Press, 1990;M. S. Asimov and C. E. Bosworth eds.,History of Civilizations of Central Asia . Vol. 4: The Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century ;Nicola Di Cosmo, Allen J. Frank, and Peter B. Golden eds., The Cambridge History of Inner Asia: The Chinggisid Age, Cambridge, Engl.: Cambridge University Press, 2009;Peter Golden, Central Asia in World History , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011。关于突厥人及其在欧亚大陆的扩张,见Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in World History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005。关于10世纪以来塔里木盆地的历史,见James A. Millward, Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang 。

[5] Davidovich, E. A., The Karakhanids , in History of Civilizations of Central Asia ,vol. 4, edited by M. S. Asimov and C. E. Bosworth, Paris: UNESCO, 1998, pp.119–43. Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in World History. 敦煌邻近于阗,有些学者表示敦煌佛教徒封闭藏经洞的原因就在于此(Rong Xinjiang, “The Nature of the Dunhuang Library Cave,” Cahiers d ’Extrême-Asie 11 (2000), pp.272–275)。对这个说法和其他说法的讨论,见Imre Galambos and Sam van Schaik, Manuscripts and Travellers , pp. 26–27。

[6] Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in World History , pp. 51, 56–75.

[7] Peter Jackson, The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History, Cambridge,Engl.: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

[8] Michal Biran, “The Mongol Transformation: From the Steppe to Eurasian Empire,” Medieval Encounters 10, nos. 1–3 (2004), pp. 339–61.关于蒙古人的书籍有很多;概述见David Morgan, The Mongols , 2nd ed., Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2007; Daniel C. Waugh, “The Golden Horde and Russia,” in Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire , edited by William W. Fitzhugh, Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch, Media, Pa.: Dino Don, 2009, pp. 173-80;Timothy May, The Mongol Conquests in World History , London: Reaktion Books, 2013。包括一系列论文和插图的入门介绍,见William W. Fitzhugh,Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch eds., Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empir, Media, Pa.: Dino Don, 2009。也可以参见牛津大学的网络资源“世界史中的蒙古人”(http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/)。托马斯·雷斯曼(Thomas Lessman)网站(“Talessman’s Atlas”)上有欧亚大陆的历史地图,表现了这些王国的兴衰,普遍做得很好,网址为http://www.worldhistorymaps.info/maps.html。

[9] 关于印度洋,见Neville Chittick, “Excavations at Aksum, 1973–74: A Preliminary Report,” Azania 9 (1974), pp.159–205; K. N. Chaudhuri, Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History from the Rise of Islam to 1750, Cambridge, Engl.: Cambridge University Press, 1985; Michael N. Pearson, The Indian Ocean 。关于非洲贸易,见John Middleton, The World of the Swahili: An African Mercantile Civilization , New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1992:M. Horton, “Artisans, Communities and Commodities: Medieval Exchanges Between Northwest India and East Africa,” Ars Orientalis 34 (2004),pp. 62–80;M. Horton and J. Middleton, The Swahili, the Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society , Oxford: Blackwell, 2000;D. Whitehouse, “East Africa and the Maritime Trade of the Indian Ocean, AD 800–1500,” in Islam in East Africa: New Sources , edited by B. S. Amoretti, Rome: Herder, 2001, pp. 41124;Philippe Beaujard, “East Africa, the Comoros Islands and Madagascar before the Sixteenth Century,” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 42 (2007),pp. 15–32。关于中国的海上贸易,见J. W. Chaffee, “Muslim Merchants and Quanzhou in the Late Yuan–Early Ming: Conjectures on the Ending of the Medieval Muslim Trade Diaspora”; Angela Schottenhammer ed., The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration , Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2008。

[10] Morris Rossabi, “The Silk Trade in China and Central Asia,” pp. 14–15. 其中一个中心就在别失八里(见“马夫”)。也可参见Thomas T. Allsen, Commodity and Exchange in the Mongol Empire: A Cultural History of Islamic Textiles ,Cambridge, Engl.: Cambridge University Press, 1997。

[11] J. R. S. Phillips, The Medieval Expansion of Europe , 2nd ed, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.关于蒙古人的角色,见Nicola Di Cosmo, “Mongols and Merchants on the Black Sea Frontiers in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Convergences and Conflicts,” in Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World , edited by Reuven Amitai and Michael Biran, Leiden: Brill, 2005, pp. 391-424。《通商指南》(La Pratica della Mercatura )是14世纪佛罗伦萨商人裴哥罗梯(Francesco Balducci Pegolotti)所写的参考书,英语译文见Henry Yule and Henri Cordier, Cathay and the Way Thither: Beijing, a Collection of Medieval Notices of China , London: Halkyut Society, 1916, pp. 137–173,或在线浏览http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/pegol.html。

[12] William H. McNeill, Plagues and Peoples , New York: Anchor Books, 1998.

[13] 关于蒙古帝国的宗教及其宗教容忍度的讨论,见D. Jackson, “The Mongols and the Faith of the Conquered,” in Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World , edited by Reuven Amitai and Michael Biran,Leiden: Brill, 2005, pp. 245-90。

[14] Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in World History , pp. 56–77.也可参见《作家》。关于伊斯兰国家的科学的讨论,见Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic Science: An Illustrated Study , Chicago: Kazi Publications, 1997;Howard R. Turner, Science in Medieval Islam: An Illustrated Introduction , Austin:University of Texas Press, 1997。

[15] Henry Yule and Henri Cordier, Cathay and the Way Thither , pp. 182, 187.

[16] Andrew Skilton, A Concise History of Buddhism , New York: Barnes and Noble,1994, pp. 183–192, 202–203.

[17] 关于佛教在印度的衰落,见Jan Yün-hua, “Buddhist Relations between India and Song China,” History of Religions 6, no. 1 (1965), pp. 24–42, and 6, no. 2(1966), pp. 135–44,以及Andrew Skilton, A Concise History of Buddhism ,pp. 143–145。

[18] 关于这次逃亡的时间点学界仍有争议,说法从8世纪初到10世纪都有;参见John R. Hinnels, “Parsi Communities i: Early History,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, 2008。http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/parsi-communities-i-early-history.

[19] AndréWink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Vol. 1: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries, Leiden: Brill,2002. Peter Jackson, The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History .

[20] Phillipson,1998, p. 127–139;Philippe Beaujard, “East Africa, the Comoros Islands and Madagascar before the Sixteenth Century”。

[21] Christopher Dawson ed., Mission to Asia, Toronto: Toronto University Press, 1998. Henry Yule and Henri Cordier, Cathay and the Way Thither ;Igor de Rachewiltz, Papal Envoys to the Great Khans , Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1971;Tim Mackintosh-Smith ed., The Travels of Ibn Battutah , London:Picador, 2003。这些文献的英语译文可在线浏览:http://depts.washington. edu/silkroad/texts/rubruck.html,http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/carpini.html。

[22] 拉班·扫马记录的英语译文,可在网上浏览:http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/sauma.html. 也可参见Morris Rossabi, Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Suama and the First Journey from China to the West, Tokyo: Kodansha,1992。

[23] W. M. Thackston trans., Rasiduddin Fazlullah ’s Jami ’u ’t-tawarikh. Compendium of Chronicles. A History of the Mongols , 3 vols, Cambridge,Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998-99. 也可参见Thomas T. Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia , Cambridge, Engl.: Cambridge University Press, 2001,大量引用了拉施都丁的记载。

[24] Margaret Medley, The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics ,Oxford: Phaidon, 1989, pp. 97–102. Robert Finlay, The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History , Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

[25] 关于8—9世纪的陶瓷贸易,见Regina Krahl et al., Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds . Washington, D. C: Smithsonian Books, 2001。马来西亚群岛东端发现一艘中国沉船,时代暂定为14 世纪,船上承载了泰国和越南的陶瓷,参见http://maritimeasia.ws/turiang/index.html。也可以参见Xu Tongjie, “The Dream and the Glory: Integral Salvage of the Nanhai No.1 Shipwreck and Its Significance,” The Silk Road 5, no. 2 (2008), pp. 16–19。

[26] Nicola Di Cosmo, “Mongols and Merchants on the Black Sea Frontiers in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Convergences and Conflicts,” p. 398.

[27] 这时大黄和茶叶都用来入药,参见Clifford M. Foust, Rhubarb: The Wondrous Drug , Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, pp. 3–17;Thomas T.Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia , pp. 120, 152。托马斯·奥森参考了拉施都丁的记载,后者花了一定的篇幅来描写茶叶。

[28] Thomas T. Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia , pp. 155, 139。也可以参见Paul B. Buell and Eugene N. Anderson, A Soup for the Qan: Chinese Dietary Medicine of the Mongol Era , Leiden: Brill, 2010。爱尔森指出最早做出雪酪的是来自撒马尔罕的景教徒。

[29] Thomas T. Allsen, Commodity and Exchange in the Mongol Empire , p. 1.

[30] 爱尔森引用了拉施都丁的记载,后者辨认出中国纸张的原料是桑树的树皮,Thomas T. Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia , pp. 177–179。中国印刷术传入欧洲的可能性,见Thomas T. Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia , pp. 180–185。

[31] 参考了10世纪回鹘文版本。参见《画匠》。

[32] Susan Whitfield and Ursula Sims-Williams eds., The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith , p. 290。

[33] Thomas T. Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia , p. 211。

[34] Vaughan, Richard, Matthew Paris , Cambridge, Engl.: Cambridge University Press., 1958, p. 145. https://archive.org/details/matthewparis012094mbp. 参见Igor de Rachewiltz, Papal Envoys to the Great Khans , p. 80。